Coronavirus: Why are international comparisons difficult?

Everyone wants to know how well their country is tackling coronavirus, compared with others. But you have to make sure you’re comparing the same things.

The United States, for example, has far more Covid-19 deaths than any other country – as of 20 April, a total of over 40,000 deaths.

But the US has a population of 330 million people.

If you take the five largest countries in Western Europe – the UK, Germany, France, Italy and Spain – their combined population is roughly 320 million.

And the total number of registered coronavirus deaths from those five countries, as of 20 April, was over 85,000 – more than twice that of the US.

So, individual statistics don’t tell the full story.

For comparisons to be useful, says Rowland Kao, professor of data science at the University of Edinburgh, there are two broad issues to consider.

“Does the underlying data mean the same thing? And does it make sense to compare two sets of numbers if the epidemiology [all the other factors surrounding the spread of the disease] is different?”

Counting deaths

Let’s look at some of the numbers first. There are differences in how countries record Covid-19 deaths.

France, for example, includes deaths in care homes in the headline numbers it produces every day, but the daily headline figures for England only include deaths in hospitals.

There’s also no accepted international standard for how you measure deaths, or their causes.

Does somebody need to have been tested for coronavirus to count towards the statistics, or are the suspicions of a doctor enough? Does the virus need to be the main cause of death, or does any mention on a death certificate count?

Are you really comparing like with like?

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

- AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

- WHAT WE DON’T KNOW How to understand the death toll

- TESTING: Can I get tested for coronavirus?

- LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

Death rates

There is a lot of focus on death rates, but there are different ways of measuring them too.

One is the ratio of deaths to confirmed cases – of all the people who test positive for coronavirus, how many go on to die?

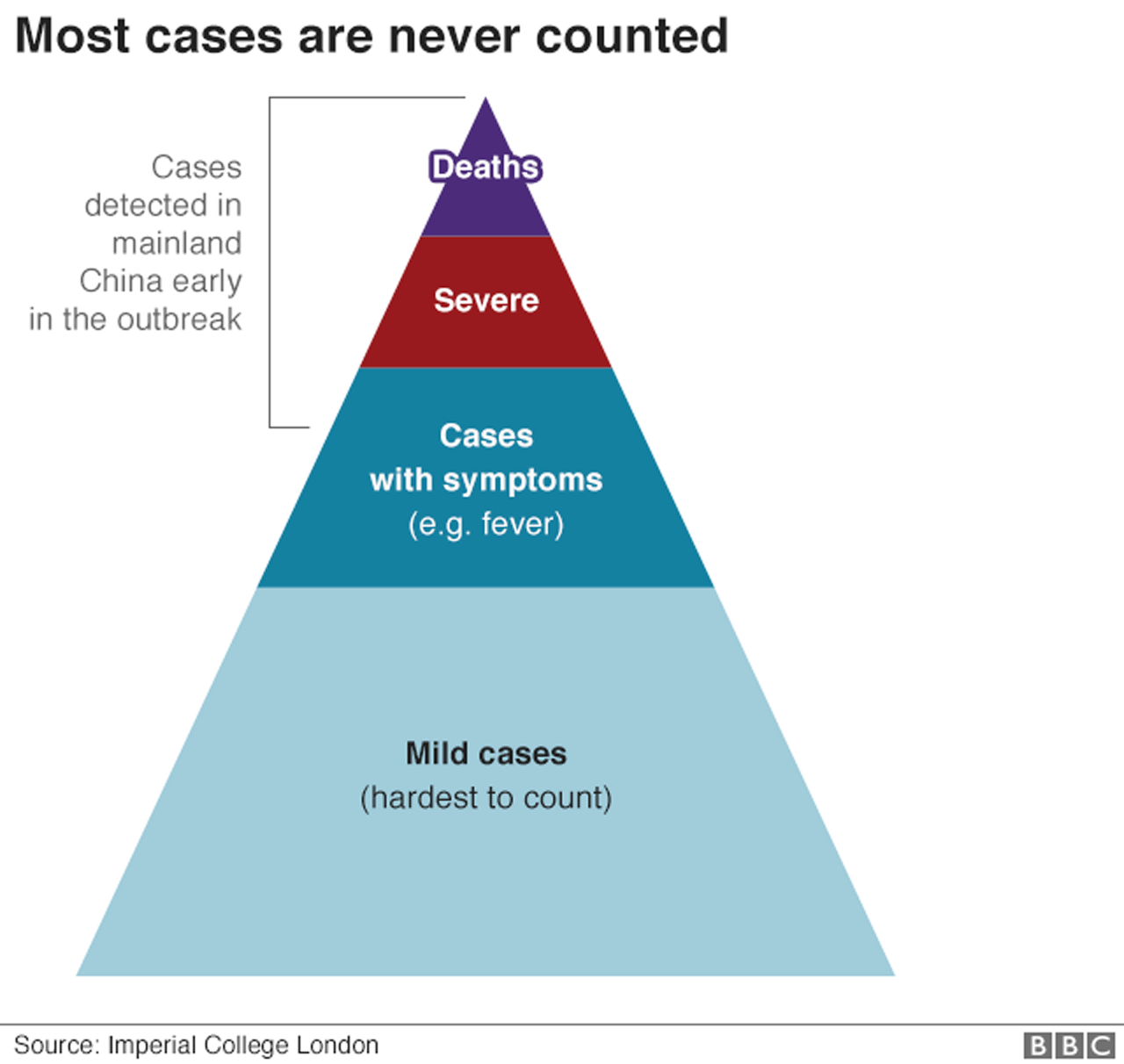

But different countries are testing in very different ways. The UK has mainly tested people who are ill enough to be admitted to hospital. That can make the death rate appear much higher than in a country which had a wider testing programme.

The more testing a country carries out, the more it will find people who have coronavirus with only mild symptoms, or perhaps no symptoms at all.

So, the death rate in confirmed cases is not the same as the overall death rate.

Another measurement is how many deaths have occurred compared with the size of a country’s population – the numbers of deaths per million people, for example.

But that is determined partly by what stage of the outbreak an individual country has reached. If a country’s first case was early in the global outbreak, then it has had longer for its death toll to grow.

The UK government compares how each country has done since recording its 50th death, but even that poses some problems.

A country that reaches 50 deaths later should have had more time to prepare for the virus and reduce the eventual death toll.

When studying these comparisons, it is also worth remembering that the vast majority of people who get infected with coronavirus will recover.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESPolitical factors

It is more difficult to have confidence in data which comes from countries with tightly controlled political systems.

Is the number of deaths recorded so far in countries like China or Iran accurate? We don’t really know.

Calculated as a number of deaths per million of its population, China’s figures are extraordinarily low, even after it revised upwards the death toll in Wuhan by 50%.

So, can we really trust the data?

Population factors

There are real differences in the populations in different countries. Demographics are particularly important – that’s things like average age, or where people live.

Comparisons have been made between the UK and the Republic of Ireland, but they are problematic. Ireland has a much lower population density, and a much larger percentage of people live in rural areas.

It makes more sense to compare Dublin City and County with an urban area in the UK of about the same size (like Merseyside) than to try to compare the two countries as a whole.

You also need to make sure you are comparing like with like in terms of age structure.

A comparison of death rates between countries in Europe and Africa wouldn’t necessarily work, because countries in Africa tend to have much younger populations.

We know that older people are much more likely to die of Covid-19.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESDifferent health services

On the other hand, most European countries have health systems that are better funded than those in most African countries.

And that will also have an effect on how badly hit a country is by coronavirus, as will factors such as how easily different cultures adjust to social distancing.

Health systems obviously play a crucial role in trying to control a pandemic, but they are not all the same.

“Do people actively seek treatment, how easy is it to get to hospitals, do you have to pay to be treated well? All of these things vary from place to place,” says Prof Andy Tatem, of the University of Southampton.

Another big factor is the level of comorbidity – this means the number of other conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease or high blood pressure – which people may already have when they get infected.

Testing

Countries that did a lot of testing early in the pandemic, and followed it up by tracing the contacts of anyone who was infected, seem to have been most successful in slowing the spread of the disease so far.

Both Germany and South Korea have had far fewer deaths than the worst affected countries.

The number of tests per head of population may be a useful statistic to predict lower fatality rates.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESBut not all testing data is the same – some countries record the number of people tested, while others record the total number of tests carried out (many people need to be tested more than once to get an accurate result).

The timing of testing, and whether tests took place mostly in hospitals or in the community, also need to be taken into account.

Germany and South Korea tested aggressively very early on, and learned a lot more about how the virus was spreading.

But Italy, which has also done a lot of tests, has suffered a relatively high numbers of deaths. Italy only substantially increased its capacity for testing after the pandemic had already taken hold. The UK is doing the same thing.

Comparisons are difficult

So, is anything useful likely to emerge from all these comparisons?

“What you want to know is why one country might be doing better than another, and what you can learn from that,” says Prof Jason Oke from the University of Oxford.

“And testing seems to be the most obvious example so far.”

But until this outbreak is over it won’t be possible to know for sure which countries have dealt with the virus better.

“That’s when we can really learn the lessons for next time,” says Prof Oke.

![]()